"Bloody Normans!" - "Maudits Anglais!"

Since July, the BBC has been running what they call a season on The Normans, plugged first by BBC History Magazine and website, then appearing as a documentary strand on BBC Two and BBC Four. I suspect the BBC use the term season rather than the more logical thematic one of "strand" due to the fact the programmes get repeated over and over across an entire calendar season and beyond - to the point it’s hard to remember after a while what you’ve seen and what you haven’t. (Clips and other info from the main programmes are still available online

here - and a set of DVDs has already appeared in the BBC’s online shop.)

This well-meaning historical onslaught now seems to be continuing with follow-up spinoff BBC4 programmes like Michael Wood’s Story Of England (tracking a village through Domesday records etc) and Churches: How to Read Them (the earliest surviving churches being Norman). It turns out that this is just the start of a 2-year interactive project, with BBC Learning (formerly BBC Schools) providing tie-in “Hands On History” educational materials, “to highlight the effect that the Normans have had on our civilisation.”

With almost no criticism to be heard of this invading, enslaving regime, the tv coverage was definitely not – to use a US hunting term – open season on Normans. However this was not always the case. For centuries, the Normans have been the heavies or villains in popular depiction, as in Scott’s Ivanhoe, which is set in the 1190s, as the Robin Hood tales usually are, so that protest is not against an “English” king but the hated new Norman regime. In an earlier post on Robin Hood, I mentioned how the Normans were so hated that to ride 100 yards from their castle was to risk an arrow through the throat from some disgruntled peon armed with the national weapon, the longbow. The later tales of Robin Hood were moved back in time-setting from a 13-14C setting to an earlier Norman one to capitalise on this, making the hero more of a freedom-fighter, the underlying idea being the Normans were such a Bad Regime that assassinating their officials was ok. (William The Conqueror was known more at the time as William the Bastard, his father known as Robert The Devil.) Setting the tales in the reign of Richard I was a masterstroke, for Robin could be heroic fighting his usurper brother evil King John, then bend his knee to rightful authority when Richard reappeared at the end, back from the Crusades and/or captivity abroad. The real Richard in fact spent almost none of his reign in England, having no interest in the place, for the original Norman colonists were just as concerned to protect or expand their Continental holdings.

This wicked-Normans-versus-benign-Saxon motif even creeps into in what is regarded as the most intelligent drama about the Normans, Jean Anouilh’s hit Broadway play Becket. The long-hard-to-see 1964 film version with Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton was also televised on BBC4 to pave the way for their “Norman” season proper (as well as issued on a Telegraph-giveaway DVD). The Guardian did one of their ‘reel history’ write-ups [reviewing historical films for their accuracy], heading it “Becket: forking Normans and a not so turbulent priest .. Misplaced Saxons, rubber swords ... they even got the cutlery wrong in this error-strewn drama…”. (The forks which are a dialogue point are actually an anachronism.)

Anouilh’s 1959 play Becket Or The Honour Of God is set in the reign of Henry II (father of kings Richard and John) and portrays Thomas Becket as an educated Saxon who depends on his Norman overlord for his position. Of course, Becket was not really Saxon at all, or he would not have been appointed Chancellor of England and Archbishop of Canterbury, especially as he was a merchant’s son. (The same sleight-of-hand was performed on later figures like the “Scots” freedom fighters William Wallace and Robert the Bruce, both descendants of Norman knights.) When the historical error was pointed to Anouilh before the first production, he declined to correct the play, no doubt as it would not work otherwise. For if Becket had been depicted as the Norman knight he was (he even went along on Norman crusades, and Victorian writers styled him as the more noble-Norman sounding “Thomas à Becket”), he would not have remained sympathetic - as most of the time he reluctantly acquiesces to his king against his own “conscience.” More recently, Becket was named, in a 2006 BBC History Magazine poll, as the 2nd-worst Englishman ever (right after Jack the Ripper), for stubbornly creating a church-state schism while using his position to enrich himself (his wealth in modern terms apparently would be £25 billion).

Nevertheless, the 1170 martyrdom-assassination of the Archbishop of Canterbury in his own Cathedral over the Xmas holidays by 4 of the king’s knights remained a right royal grade-A public-relations disaster, Henry having to allow himself to be flogged by monks as part of his penance - as the film shows. Whereas the Normans’ 1066 invasion had been endorsed by the Pope as a holy crusade, the assassination of this “turbulent” priest (some sources have Henry saying “Will no one rid me or this troublesome priest?") became a turning point. It meant the ending of Norman supreme feudal state power due to church opposition. Henry was excommunicated and Becket was made a martyred saint, and his tomb was the #1 English pilgrim destination for centuries, as in Chaucer's late-14C Canterbury Tales.

This is also the subject of the other serious play on the topic (based partly on a surviving eye-witness account by a young cleric), a 1935 religious pageant verse drama by poet T. S. Eliot. (Despite his bleak modernist Waste-Land views, Eliot was a keen Church of England supporter). Eliot’s Murder In The Cathedral is still acted out in churches and schools across Britain despite the complexity of its text. Though we’ve had several dramas about 1066 in the past year (covered in earlier posts), still to come is a Hollywood production of a stage play about the foursome who killed Becket and had to go onto hiding: Four Knights, from what we might term the Blackadder School Of History, with ribald jokes mixed in with mordant reflections.)

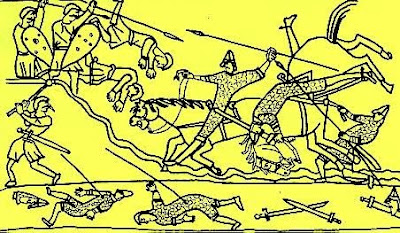

The Normans of course had a bad rep going back to the days [8-11C] when they were the roving Norse or Northmen, before one branch relocated from Denmark and Norway to settle among the coastal Franks in north-western Neustria, renaming it Normandy, and merging their language with Frankish or early French. (Thus after 1066, Germanic Old English became the French-influenced Middle English.) There is said to have been a monastic prayer from the days the raiding Northmen or Norsemen sea-rovers, the so-called Vikings (this just means "inlet-ers") who pillaged European coasts for centuries: "Protect Us O Lord, from the wrath of the Northmen." (You can see and hear this apocryphal prayer spoken by Orson Welles in the 1958 film The Vikings, in the explanatory scene-setting animated prologue cleverly based on Bayeux Tapestry imagery.)

The next step was for the branch which left their base in Normandy to abandon the hated Norman (from the Latin for Norse /North-men) identity and rebrand themselves completely (rather like the present royal family changing their surname in WWI from von Saxe-Coburg to Windsor). The Norman identity in a sense began to be abandoned as early as 1100, when William the Conqueror’s unpopular (anti-clerical) son and heir William Rufus fell dead with an arrow in him in the New Forest, and his brother rode off and left the body lying there in order to quickly secure the crown as Henry I. (The legitimate heirs were another branch of the family, his brother Robert’s, whom Henry put in prison for life.) A 19-year civil war over succession, known as The Anarchy, followed Henry I’s death, and when Henry II took over, he adopted a new name for his branch of the royal tree. The family’s actual dynastic name was Anjou, whereas the new dynastic name, Plantagenet, which they adopted (later as a surname) came from a French word, a nickname for Henry II’s father after a sprig of broom he wore in his hat. It was adopted by the Angevin branch of the dynasty, suggesting a metaphor of a transplanted gens or people. (The French word gens implies a noble people defined by their role in history, so there is a special phrase for “ordinary people” - gens sans histoires: people without a history, associated with people of the servant class, which is what the English people had suddenly become.)

What have the Normans ever done for us?

All this new tv and media-kit coverage seems by way of rehabilitating the reputation of the Normans, a sort of what-have-the-Romans /Normans ever-done-for-us riposte to their brutal reputation in historical records. Our interest here is in codex books, and the Norman Conquest of course led to an immense national land-holdings project culminating in several bound codex volumes known collectively as the Domesday Book. This has recently been put online in more simplified form for the general public (earlier versions being for academics). The BBC season had a programme on the Domesday Book as the definitive guide to the new Norman feudal allocations in 1086.

Over lunch with a local archivist and historian, I was discussing this issue of the Normans supposedly “giving” us civilised features (including forks), and the way the season seemed as uncritical about the Normans as tv coverage of the Romans, who supposedly also brought civilisation with them. (Both are credited with introducing rabbits to Britain; the remains of a Romano-British era rabbit dinner were unearthed this spring by a county council archaeological unit in Norfolk.) He pointed out the Domesday Book does not in fact really show a snapshot of Norman England at all but one of pre-Conquest England. It shows how well Saxon England was run as a church-state partnership, much of it a legacy from the days of Alfred the Great. It’s not so much an example of a new more competent Norman administration but the exploiting of the work of an earlier civil service.

In fact, because Harold of Wessex who opposed the 1066 invasion was officially persona non grata (declared a perjurer and blaspheming heretic over a loyalty oath he supposedly swore to William over a saint’s bones hidden from him beneath a table-cloth), his coronation and acts like his land-holding appointments were considered legally void, and thus Domesday omits his reign and portrays land-holdings as they existed in the time of his predecessor. Coincidentally, there is another new related searchable database of Anglo-Saxon names of persons and places, put online in August, with the wonderful title The Prosopography Of Anglo-Saxon England. (A prosopography is a sort of collective comparative biography, a historian’s method used to establish how a group of people lived etc.; the database is a searchable one so you can see all the manuscript references to e.g. Cerdic, official founder of the kingdom of Wessex – despite his name being merely an Anglicised Celtic one -Caradoc.)

The BBC coverage did mention the so-called Harrying of the North, a virtual genocide of Nazi-style reprisals on towns and villages resisting the Norman yoke (and was followed by the Norman Conquest of Ireland) - though this did not stop at least one pro-Norman English historian from saying how “it only took the Normans a single day to conquer England,” i.e. at Hastings. I’ve read statements by military historians that on the contrary if Harold had been able to hold out for just one more hour, the Normans would have had to withdraw to their boats.

There was little BBC coverage either, of the way the new Norman regime’s official commemoration narrative, the Bayeux Tapestry, was a self-justifying propaganda account of the Conquest whose details are suspect – an 11th-C dodgy dossier, as one wag put it. One example of this was the most famous detail, Harold’s arrow-in-the-eye demise at the Battle of Hastings, as (apparently) depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, despite this being contradicted by surviving codex accounts. (The controversial arrow-in-the-eye moment from the Tapestry is used as the cover of the new BBC DVD.) I’ve blogged before regarding a surviving codex account, the Vita Haroldi, which claims that Harold even survived the Battle, nursed by a Saracen woman who was a healer. (Saracen women were sometimes brought back to England from the Crusades - Becket’s mother was said to have been one, though this was left out the film version of Anouilh's play, perhaps as it is fanciful – she was as Norman as his father). Harold became a non-person, erased from history as a wandering pilgrim, his mutilated face concealed behind a cloth mask. This odd survival legend [earlier blog entry here] was at the very least also a subversive whispering against the new Norman regime lasting up the Normans’ rebranding themselves as Plantagenets.

A more significant aspect of the post-Conquest “rehabilitation” of the Normans as Plantagenets which was not delved into was the Celtic Breton influence on the Arthurian legend. The season did include a programme called The Making Of King Arthur, which supposedly “reveals that King Arthur is not the great national hero he is usually considered to be. He's a fickle and transitory character who was appropriated by the Normans to justify their conquest, he was cuckolded when French writers began adapting the story and it took Thomas Malory's masterpiece of English literature, Le Mort d'Arthur, to restore dignity and reclaim him as the national hero we know today.”

This self-serving farrago is designed to give the almost-culture-free Normans credit for the development of Arthurian Romance. Whether or not he ever existed as an actual king or general, Arthur was depicted as a heroic national saviour in chronicle and legend well before the Norman-French court poets got their hands on the legend. In fact, it was no doubt because his name was so well-known that fabled “King Arthur” became the anchor-point in terms of scene-setting for the fashionable new genre of knightly romances that were otherwise quite fantastical. And Malory lived several centuries too late to be regarded as a Norman. In any case, he was little more than a compiler and translator, whose work was done for the first printed compilation of the various stories into a single narrative, by England’s pioneer printer, Caxton, in 1485.

This very year is regarded as the end of the Middle Ages, and Caxton’s preface says he is publishing the book after being pressured by various noblemen who claimed Arthur was a great (and historical, not fictional) Christian ruler. Arthurian romances had political-propaganda potential, and it was this that probably got the earlier romans d’aventures sponsored at the English court of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. It’s thought the code of chivalry that these romances espouse as a behavioural model was invented to try to control knights from the new Norman landholding dynasties who were otherwise out of control, killing anyone who got in their way.

These courtly romances may have been written in Old French, but the thematic material was Celtic-British: it came largely from Breton conteurs (minstrels) whose predecessors had brought the original tales of Arthur with them from the West Country when they fled across the Channel to Brittany and Normandy to escape the Saxon takeover of southern Britain. It is estimated that around a third of the “Normans” arriving in 1066 were in fact Bretons, who would regard themselves as returning to their old mother country. (This is now thought to include the parents of Geoffrey of Monmouth, who around 1135 wrote in Latin prose a History Of The Kings Of Britain, the pseudo-history which really launched Arthur as a claimed historical ruler of a great kingdom - the earlier Arthur was more of a general.) The Breton presence was useful to the relatively uncultured new Norman regime as they tried to pass themselves off as a legitimate regime, based on an ancestry older than any Saxon presence.

But if anything, it was the wily Breton conteurs and Welsh nationalists who were putting one over on the uncultured Normans, who were never accepted as British. The Breton conteurs and Welsh clerics at the Norman court could read Celtic script (Welsh or Breton) and used earlier Celtic-British folktale motifs which had been maintained at the courts of the Dark Ages exiles in their colony of Brittany or “Little Britain” where the place names were based on West Country ones, like Cornouaille from Cornwall. (Geoffrey Arthur alias Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed his work was based on "an old book in the British tongue" - which has never been identified.)

For instance, in the programme blurb reference to Arthur being turned into a cuckold, i.e. Guenevere being unfaithful with Lancelot, this was not an invention of Norman-French writers, but a reflection of an old Celtic-British social practice. Centuries before, Julius Caesar on visiting Britain mentioned that among the Britons the 10-12 men of a warband would often agree to share a wife (not a servant or slave), with any paternity designated to her first consort. This was probably inspired by a shortage of women to travel with a warband, but something similar is known to have survived in the free non-Romanised north, where Pictish noblewomen consorted, apparently at their own wish, with the warriors at court. In fact their royal descent may have been matrilinear – with no son apparently succeeding his father in the Pictish Kings-list codex – the mother was more important, the identity of the actual father probably being unclear due to this practice. As one Pictish princess visiting Rome told some shocked Roman matrons, whereas Roman women consorted secretly with the vilest of men, Pictish noblewomen consorted openly with the finest. Though not much is known of the Picts, I’ve read that the Pictish word “cing” meant not a monarch but a champion, so here we would have the cultural basis of Lancelot the court champion winning Guinevere’s favour over the now older former battle champion turned sedentary monarch, Arthur.

The Norman-founded dynasty lost their original Continental holdings under militarily weak kings. Kings like John and Edward II, who were unwilling or unable to expend sufficient resources to fight the French in what became known as the 100 Years War, which with periodic English victories like Agincourt in 1415 lasted over a century. This lengthy war was at once followed by a dynastic civil war lasting almost as long, known as the Wars Of The Roses. This split the post-Norman Plantagenet dynasty again into two branches or forks, the rival Houses of Lancaster and York, based on yet another dispute over succession between “cadet” branches. (The Lancastrians were supposedly the Plantagenet descendants, but there were Plantagenets on both sides: the Yorkist leader, the father of Richard III, was Richard Plantagenet.)

It ended with Richard III’s crown falling under a bush at Bosworth in 1485, the same year as Caxton printed the final and definitive edition of the Arthurian legend at the behest of those unnamed noblemen. (Malory was dead by then, having spent part of the civil war in prison for various un-knightly offenses, and it was there he supposedly researched and wrote his Morte d’Arthur compilation.) Henry II’s attempt to leave the hated Norman stigma behind backfired because of his own misconduct. His role in getting Becket killed led to people muttering the dynasty was “the devil’s brood,” cursed by God. Later around 1200, Henry and Eleanor’s joint role in killing off their late son Geoffrey of Anjou’s teenage son Prince Arthur [1187-1203?] of Brittany when he got involved in the dynastic feud led to more whispering against the dynasty. (Henry and Eleanor’s son King John usually gets the credit for castrating, blinding and drowning the imprisoned teenage Arthur.)

This in 1485, all this came to a conclusion with both the end of the Wars Of The Roses and – perhaps no coincidence – the first printed, “definitive” version of the Arthurian cycle. The odd title change Caxton imposed on Malory’s vast compilation The hoole booke of kyng Arthur & of his noble knyghtes of the rounde table, to emphasize only the last act, may have been political. There had already been a final “death of Arthur” volume, which Malory had used for his final section, the prose post-Vulgate [Vulgate = not in Latin] work called “Le Mort le Roi Artu” (usually since known just as the Mort Artu).

This was a disillusioned mid-13C. take on the legend (with an aged Arthur etc), which came with a preface saying it had been commissioned by Henry II himself to finish the story up to death of Arthur et al. It ends with a note saying the matter has now been bought to “a proper conclusion” and that “no one ever afterwards can add anything to the story that is not complete falsehood.” It was clearly meant to forestall any unauthorised follow-ups. Henry II was long dead by then, but in his lifetime may have felt the Arthurian cycle an embarrassment inviting comparisons between “emperor” Arthur, mighty and wise king of 30 domains, and Henry, accursed excommunicated king of England, Ireland, and half France, and unsuccessful Crusader ruler of Jerusalem, not to mention failed husband and father. (The play The Lion In Winter, filmed in 1968, with Peter O’Toole this time as a post-Becket Henry some 20 years on, makes a meal out of his dysfunctional family situation.)

The court-sponsored Arthurian Romances depicted an ideal world no real king could ever come close to living up to.

Caxton’s 1485 Morte d’Arthur, produced at the insistence of unnamed nobles (Geoffrey Ashe has suggested this was political, from high up) was most likely another attempt at ending a propaganda cycle that had outlived its usefulness and largely backfired, the comparison with chivalrous Arthur only drawing attention to the Plantagenet line’s feet of clay. It was the end of an era. In 1485, the final successor of all this splitting (perhaps we should sat forking) into rival dynastic branches, crowned as Henry VII, claimed kingship largely based on his Welsh ‘Tewdr’ or Tudor roots on the distaff side, the House of Plantagenet being extinct in its male royal line due to all the centuries of bloody disputes. Though Henry’s chosen heir, suitably named Arthur, died young, the “House Of Tudor” would prove a more long-lasting claim, with the heir to the throne today still known as the Prince Of Wales.