Last time, I said we would take a look at the Coelbook's account of the 'thorny matter of Glastonbury', a pun that reflects the inherently prickly nature of the subject. For the so-called Glastonbury legends of the holy thorn tree being planted there by Joseph of Arimatheia etc are not, as some academics would have you believe, entirely the invention of eccentric Edwardian vicars promoting the 'British Israelite' idea, or of New Age hippies with woolly ideas. (In 1994, I attended a U. Of Bristol course on Glastonbury archaeo-history, in which the professor referred to such types as “the enemy” who would “try to get you to believe anything,” and who had “ruined the place.”)

The claim that Christianity arrived in Britain via Glastonbury in the 1st-C AD was part of a more general longstanding claim by the Church Of Britain that it was older, and thus had precedence over, the Church Of Rome. Though the original Celtic Church Of Britain was legislatively replaced by the formative English or Saxon Church in 664, the claim was backed by certain early bishops and saints who wrote church history, and maintained until at least the 15th C. (At some point Glastonbury acquired the epithet “Roma Secunda.”) The claim was followed by England setting up its own church, separate from Rome, in Henry VIII's Reformation and Dissolution of the 1530s-40s, which saw Glastonbury looted of its treasures and its last abbot hanged from the Tor by Henry's tame church officials.

The Coelbook's survival, as mentioned previously, was credited by its guardians due to its being spirited away after the disastrous Glastonbury Abbey fire of 1184, which the preface claims was arson by the king's minions to purge the place of its heretical, mystical texts. Nothing is known of the circumstances of the 1184 fire, which destroyed the original wattle church (by then encased to preserve it) and the old Saxon Abbey. But within a few years, the Abbey was certainly promoting itself as a place holding other kinds of treasure. It became a destination for pilgrims wanting to see the graves and relics of various celebrities. This included an ancient (deep-down) hollow-log coffin excavated during rebuilding in 1191, attributed to legendary Arthur on the basis of the inscription on a lead cross supposedly found atop the grave. (The inscribed cross, with a suspiciously explicit text carved in anachronistic early-medieval Latin, is pictured in our sidebar.) Arthur is not mentioned in the Coelbook, and the Abbey itself in its earliest surviving official history makes no mention of him.

Nevertheless, the basics of the JoA legend are there in the works of the Abbey's two-time chronicler William Of Malmesbury, a monkish librarian. He mentions “documents of no small credit” as his source; these have never been identified, but I can't help wondering if we now have a candidate, for the handwritten Coelbook collection was supposedly then stored in the Abbey.

Mediaeval kings had a strained relationship with Rome, with the threat of the Pope excommunicating England looming up repeatedly from King John onwards. The king at the time of the 1184 fire, Henry II, had a precarious relationship with Rome, coming to a head in 1170 when he intemperately incited his barons into a fatal attempt to seize his Archbishop, Becket, in Canterbury Cathedral over the Xmas holidays. Henry himself was excommunicated and there was nearly civil war. In the end, Henry had to do public penance, walking barefoot in a sack-cloth through Canterbury and being scourged by 80 monks. I can well understand how he would have wanted to head off any more trouble with Rome. As far as I know, Henry has never been implicated by historians in the 1184 fire, though his insistence on having the Abbey magnificently rebuilt at his own personal expense might be construed today as suspicious.

Now, to the Coelbook's account of the arrival of Christianity in Britain, via Glastonbury.

--The account says that Joseph and his party sailed on a “ship of Tarsis” (cf the Bible's “ships of Tarshish”) a year after the Crucifixion, which other evidence here indicates as AD 30+1 = AD 31, though a later reference says they had various disasters and delays en route and didn't actually arrive until the 3rd year, ie AD 33. (Church historian St Gildas the Wise, whose account is the only contemporary account to survive from the Dark Ages, said Christianity came to Britain in the latter part of the reign of Tiberius, who died AD 37). The party sailed around Cornwall (there are several familiar place-names) to Siluria [S. Wales] and thence east to the place beyond Sabrin [Severn, Latin Sabrina] called Summerland [Somerset]. Reaching the Kingdom of Arviragus - reputedly the brother or anti-Roman Silurian war-leader Caractacus or Caradoc - (here called “Caradew”), they “came under the mantle of the High Druid of the south whose ear was inclined towards them,” and so they were given land near “the Isle of Departure.”

Glastonbury was an Iron Age tidal port, with traces of a stone wharf found below Wearyall Hill where in local legend JoA planted his staff. But it turns out this is not what Isle of Departure means: the text says it was where the dying are taken to be prepared for death, with the lake a kind of looking-glass portal into the Otherworld - an aspect of British Celtic belief mentioned in other sources. (“Here was the resting place for the souls of the dead, where they received their last sustenance before passing through the glass wall”.) This offers an alternative new explanation for the ancient references elsewhere to Glastonbury as Ynys Witrin or “Isle Of Glass.” There is a description of the women who tend the dead and dying as living in houses on stilts, ie in a “lake village”, something which is archaeologically attested nearby.

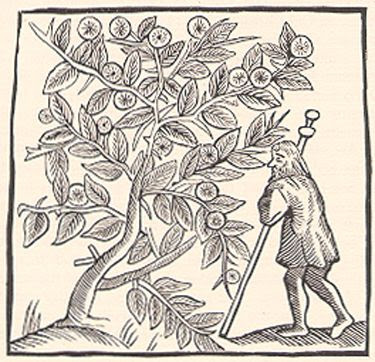

A second passage, by one 'Aristolas,' says when Joseph of Abramatha [sic] arrived, he found the king in need of advice, for his own head priest, Trowtis, Chief of the Druthin, “was away at the meeting place of his god, where he came in a wondrous way every nineteen years. There, the ceremony lasted three moons.” (This of course is where we came in, so to speak, with this reference to an apparent Iron Age survival, described by a Greek traveller, of the rites of Apollo at a centre like Stonehenge or Avebury every 19th year - see earlier post “The Lost City of Apollo”). The king lets Joseph meet with Trowtis “at the place now called Henmehew, because of the strange tree that grows there.” Here we may have our first reference to the Glastonbury Thorn, whose surviving offspring [see photo] have been classed either as “a Palestinian variety” or more recently as a hybrid hawthorn.

The local sub-king, who has reluctantly received them due to Arviragus's influence, sets up a priestly debate, held “in the place called Nematon” (a nemeton is a Druid-style sacred grove) over whether to allow the strangers to stay on some unhealthy swampland by the lake village at the edge of the tidal port, thinking they will be refused even that. But Joseph, “called Ilyid by the people here” (this probably means just a man of Judea, the J being pronounced outside of modern English as an I- or Y, cf German Yiddish) carries the debate. So the king “gave the strangers land beside the Summerhouse of the King, which could be reached by ships. Inland from here, the gifted land extended to the tree now called the Great Oak which still stands, and thence to the hill south of the residence where Ilyid, being wearied, rested against a great stone. Beyond this was an avenue of standing trees and oak trees placed one and one, and the gifted land came up against this. It extended southward to the holy vineyard which was fenced about. The fruit of these vines was small and bitter in the mouth. The strangers built huts for shelter on the hillside, high enough to be free of the tides. … Ilyid persevered and while later the people still would not believe that The God of whom he spoke was more powerful than their gods, they would sit around and listen to his stories.

“Now, when the strangers were granted the land, the Druthin disputed this with the king and said that they wanted a divine sign that their gods approved. Ilyid said, "Give me but half a year". At the witnessing of this the Druthin set up a holistone and Ilyid struck his staff into the soil to mark the covenant. The following Eve of Summer there was a gathering and it was found that a small green shoot was coming up from the ground beside the staff, which was an offshoot of the staff. The king decreed that this was a sign that the land accepted the strangers, but these took it as a sign that what they taught fell on fertile ground and would take root.”

The party argued that if they “could they live where no one else could because of the spirits, then their holiness would be established before all the people. The strangers were sorely tried by the Druids, but the spirits troubled them not. Nor did the sickness of the place come upon them, and the people wondered.” The king's niece, known as Islass the Dreamer, who worked on the Isle of Departure, and “was sacred to the guardian of this place” became the first convert, and was evidently given care of “the secret of the Holy Hawthorn. What this may be, none can know now. It is said that when the Druthin murmured against the staff of Ilyid, she placed a twig in water and it flowered. Here, in this holy place, under the direct guidance of God, our father founded the first church in Britain. It is said it was not built by human hands, which is true, and from here shall come that which will be the salvation of mankind in the years to come. Here was the resting place for the souls of the dead, where they received their last sustenance before passing through the glass wall. From here ran the old road to the place of light….”

… Well, this is all fascinating, but there are problems when you try to plot these and other topographical details out on the historical map of Glastonbury. (For example, the Lake Village apparently stood on the other side of the valley from Wearyall Hill.) My notes from that 1994 uni course are sketchy, and I think a field trip is called for, before we take this any further.